The cervical spine’s mid-level segments, particularly at C3-C4, represent a critical anatomical region where degenerative changes frequently manifest as disc osteophyte complexes. This condition involves the development of bony outgrowths (osteophytes) in conjunction with intervertebral disc pathology, creating a constellation of symptoms that can significantly impact neural structures and overall cervical function. Understanding the intricate pathophysiology, clinical presentations, and management strategies for C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes is essential for healthcare professionals managing cervical spine disorders. The C3-C4 level’s unique biomechanical properties and anatomical characteristics make it particularly susceptible to degenerative changes, often resulting in foraminal narrowing and potential neural compression that requires comprehensive evaluation and targeted treatment approaches.

Cervical spine anatomy and C3-C4 vertebral segment structure

C3 vertebra morphological characteristics and articular facets

The third cervical vertebra exhibits distinctive anatomical features that contribute to its functional capacity within the cervical spine’s kinetic chain. The C3 vertebral body demonstrates a rectangular configuration with slightly elevated lateral margins, creating the characteristic uncinate processes that articulate with the adjacent vertebral segments. These bony projections serve as critical anatomical landmarks and play a fundamental role in limiting lateral flexion whilst maintaining sagittal plane mobility. The superior and inferior articular facets of C3 are oriented approximately 45 degrees from the horizontal plane, facilitating the complex three-dimensional movements characteristic of cervical spine biomechanics.

C4 vertebra anatomical features and uncinate process formation

The fourth cervical vertebra shares morphological similarities with C3 but demonstrates subtle variations that influence the biomechanical behaviour of the C3-C4 motion segment. The C4 vertebral body typically measures slightly larger than its superior counterpart, reflecting the progressive increase in size as the cervical spine transitions towards the thoracic region. The uncinate processes of C4 are particularly well-developed, forming the uncovertebral joints (joints of Luschka) with the bevelled edges of the C3 vertebral body. These articulations serve as secondary stabilising structures that limit excessive lateral translation and contribute to the overall mechanical stability of the cervical motion segment.

Intervertebral disc composition at Mid-Cervical level

The C3-C4 intervertebral disc exhibits the typical fibrocartilaginous structure characteristic of cervical discs, comprising a central nucleus pulposus surrounded by concentric layers of annulus fibrosus. However, the cervical discs differ significantly from their lumbar counterparts in terms of size, shape, and biomechanical properties. The nucleus pulposus at the C3-C4 level contains a higher water content compared to lower cervical segments, contributing to its shock-absorbing capabilities and flexibility. The annulus fibrosus demonstrates a posterior thinning that makes this region particularly vulnerable to degenerative changes and subsequent osteophyte formation as the aging process progresses.

Zygapophysial joint mechanics between C3-C4 segments

The zygapophysial joints, commonly referred to as facet joints, between C3 and C4 vertebrae demonstrate unique biomechanical characteristics that influence the motion patterns and load distribution within this segment. These synovial joints are oriented in an oblique plane, typically ranging from 35 to 55 degrees from the horizontal, allowing for coupled motion patterns that are characteristic of cervical spine kinematics. The joint capsules are relatively lax compared to thoracic and lumbar facet joints, permitting greater range of motion but potentially predisposing the segment to instability under pathological conditions. The articular cartilage covering the facet joint surfaces is relatively thin, making these structures susceptible to degenerative changes that can contribute to the development of facet joint osteophytes and subsequent neural compression.

Pathophysiology of disc osteophyte complex formation

Degenerative cascade theory and Kirkaldy-Willis model

The development of disc osteophyte complexes at the C3-C4 level follows the well-established degenerative cascade described by Kirkaldy-Willis, which progresses through three distinct phases: dysfunction, instability, and stabilisation. During the initial dysfunction phase, repetitive microtrauma and age-related changes lead to alterations in disc composition, particularly a reduction in proteoglycan content and water retention capacity within the nucleus pulposus. This biochemical degradation results in decreased disc height and altered load distribution across the motion segment. The subsequent instability phase is characterised by further disc degeneration, development of annular tears, and increased segmental motion that exceeds physiological limits. Compensatory mechanisms during this phase include the formation of marginal osteophytes as the body attempts to restabilise the affected motion segment.

Osteophyte genesis through endochondral ossification

The formation of osteophytes at the C3-C4 level represents a complex biological process involving endochondral ossification pathways similar to those observed during embryonic skeletal development. Initial osteophyte formation begins with the transformation of fibrous tissue at the vertebral margins into fibrocartilage, followed by progressive calcification and eventual ossification. This process is mediated by various growth factors, including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which stimulate chondrocyte proliferation and subsequent bone formation. The mechanical stress concentrations that develop at the vertebral endplate margins due to altered load distribution serve as the primary stimulus for this adaptive remodelling response . Research indicates that osteophyte formation typically occurs first at the anterior vertebral margins before progressing to posterior regions where neural compression becomes more likely.

The formation of vertebral osteophytes represents the body’s attempt to increase the contact surface area and restore stability to a degenerated motion segment, but this adaptive response can paradoxically result in neural compression and symptomatic presentations.

Biomechanical stress distribution in cervical motion segments

The unique biomechanical environment at the C3-C4 level creates specific stress patterns that predispose this segment to degenerative changes and subsequent osteophyte formation. Unlike the upper cervical segments (C1-C2) which are specialised for rotation, or the lower cervical segments (C5-C7) which bear greater axial loads, the C3-C4 segment functions as a transitional zone with complex motion patterns. During normal cervical spine movement, the C3-C4 segment experiences combined loading patterns including compression, tension, shear, and torsional forces. The presence of degenerative changes alters these stress distributions, creating areas of stress concentration that can accelerate the degenerative process. Finite element analysis studies have demonstrated that disc degeneration at the C3-C4 level results in increased stress transfer to the facet joints and uncovertebral joints, contributing to the development of osteophytes at multiple anatomical sites within the motion segment.

Inflammatory mediators in spondylotic changes

The pathogenesis of disc osteophyte complexes involves a complex interplay of inflammatory mediators that perpetuate the degenerative process and contribute to symptom development. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), play crucial roles in promoting disc matrix degradation and stimulating osteophyte formation. These inflammatory mediators activate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that break down collagen and proteoglycans within the disc structure. Simultaneously, inflammatory cytokines stimulate the expression of osteogenic factors that promote bone formation at the vertebral margins. The resulting inflammatory environment not only accelerates structural degeneration but also contributes to nociceptive sensitisation , potentially explaining why some patients with relatively minor structural changes experience significant symptomatology whilst others with more advanced degenerative changes remain asymptomatic.

Clinical manifestations and neurological compression patterns

C4 nerve root radiculopathy symptomatology

Compression of the C4 nerve root due to disc osteophyte complex formation results in a characteristic pattern of symptoms that reflects the anatomical distribution and functional responsibilities of this neural structure. The C4 nerve root primarily innervates the levator scapulae, rhomboids, and portions of the diaphragm through the phrenic nerve contribution. Patients typically present with neck pain and stiffness that may radiate to the occipital region, creating headache patterns that can be mistaken for tension-type or cervicogenic headaches. The referred pain distribution often extends to the superior aspect of the shoulder and may be associated with trapezius muscle spasm and tenderness. In severe cases, C4 nerve root compression can result in diaphragmatic dysfunction, though this is relatively rare and typically requires significant neural compromise.

Sensory symptoms associated with C4 radiculopathy include numbness or paraesthesias extending from the neck to the supraclavicular region and upper chest area. These sensory disturbances may be subtle and intermittent, particularly in the early stages of neural compression. Motor weakness, when present, typically manifests as difficulty with shoulder elevation and may be accompanied by scapular winging due to serratus anterior or rhomboid weakness. The clinical presentation can be further complicated by the presence of myofascial trigger points in the cervical and upper thoracic musculature, which develop as compensatory responses to altered movement patterns and prolonged muscle tension.

Spinal cord compression at C3-C4 level

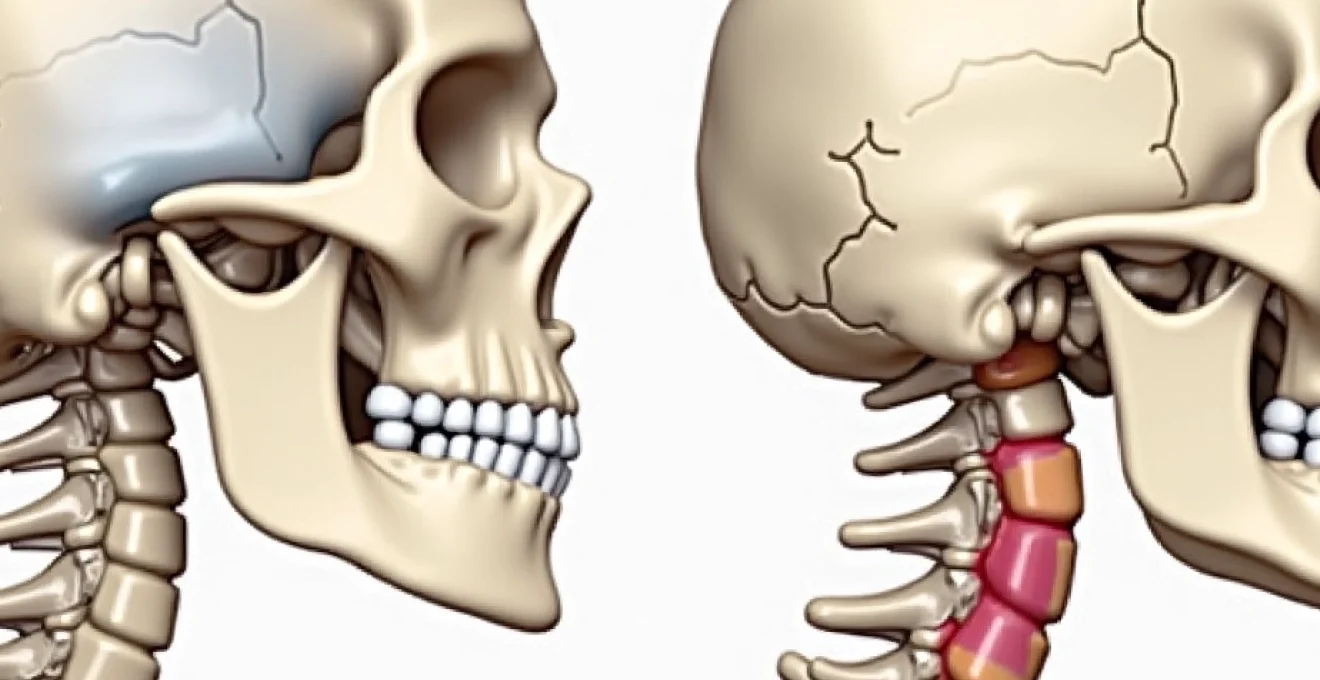

Central disc osteophyte complexes at the C3-C4 level can result in spinal cord compression, leading to the development of cervical myelopathy with potentially serious neurological consequences. The cervical spinal cord at this level contains critical ascending and descending neural pathways, including the corticospinal tracts responsible for motor function and the dorsal columns mediating proprioception and fine touch sensation. Early myelopathic changes may be subtle and include loss of manual dexterity, particularly affecting fine motor tasks such as handwriting or buttoning clothing. Patients often report subjective weakness or clumsiness in their hands, which may progress to objective motor deficits if compression continues.

Advanced cervical myelopathy due to C3-C4 disc osteophyte complex can manifest as upper motor neuron signs including hyperreflexia, positive Hoffman’s sign, and the presence of pathological reflexes such as the Babinski sign. Gait disturbances may develop, characterised by spastic gait patterns with reduced stride length and increased fall risk. Bladder and bowel dysfunction, whilst less common at this cervical level compared to more caudal compression sites, can occur in severe cases and represents a surgical emergency requiring immediate decompression. The natural history of cervical myelopathy is typically one of stepwise deterioration with periods of stability interspersed with episodes of neurological decline.

Cervical myelopathy secondary to central canal stenosis

Central canal stenosis at the C3-C4 level due to disc osteophyte complex formation represents one of the most serious complications of cervical spondylosis. The development of central stenosis typically involves multiple pathological processes occurring simultaneously, including disc bulging, osteophyte formation, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and facet joint arthropathy. These combined factors result in a reduction of the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal, creating a hostile environment for the cervical spinal cord. The critical threshold for symptomatic central stenosis is generally considered to be a canal diameter of less than 10-12mm, though individual variations in cord size and adaptive capacity can influence symptom development.

The clinical presentation of central canal stenosis often includes a combination of motor, sensory, and autonomic symptoms that can significantly impact quality of life. Lhermitte’s sign , characterised by electrical shock-like sensations radiating down the spine and into the extremities with neck flexion, is a pathognomonic sign of cervical myelopathy. Patients may also experience temperature sensation abnormalities, with particular difficulty discriminating between hot and cold stimuli in the hands and feet. The development of central canal stenosis can be insidious, with symptoms progressing gradually over months to years, making early recognition challenging but crucial for optimal treatment outcomes.

Vertebral artery compromise and vascular insufficiency

Large osteophytes developing at the C3-C4 level can potentially compress the vertebral arteries as they course through the transverse foramina of the cervical vertebrae. Vertebral artery compression, whilst relatively uncommon at this level compared to the atlantoaxial region, can result in symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency including dizziness, vertigo, visual disturbances, and drop attacks. The vertebral arteries at the C3-C4 level are typically well-protected within the transverse foramina, but large uncovertebral osteophytes or laterally projecting disc osteophyte complexes can encroach upon the arterial lumen, particularly during neck rotation or extension movements.

Clinical assessment of potential vertebral artery compromise requires careful evaluation of symptoms in relation to neck positioning and movement patterns. Patients may report position-dependent symptoms that worsen with neck extension or rotation to one side, suggesting dynamic compression of the vertebral artery. Advanced imaging modalities, including CT angiography or MR angiography, may be necessary to evaluate arterial patency and identify areas of stenosis. The management of vertebral artery compression associated with disc osteophyte complexes requires careful consideration of both neurological and vascular factors, as surgical intervention must address both the neural decompression and preservation of arterial flow.

Understanding the complex relationship between structural pathology and clinical symptoms is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies that address both neural compression and vascular compromise in disc osteophyte complexes.

Diagnostic imaging protocols for C3-C4 assessment

Comprehensive evaluation of disc osteophyte complexes at the C3-C4 level requires a systematic approach to diagnostic imaging that incorporates multiple modalities to fully characterise the extent of pathology and guide treatment decisions. Plain radiography serves as the initial imaging study and provides valuable information regarding overall cervical spine alignment, disc height loss, and the presence of osteophytes. Lateral cervical spine radiographs obtained in neutral, flexion, and extension positions allow assessment of segmental instability and dynamic changes at the C3-C4 level. Anteroposterior radiographs can reveal the presence of uncovertebral osteophytes and any associated foraminal narrowing, whilst oblique projections provide optimal visualisation of the neural foramina and facet joint morphology.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents the gold standard for evaluating soft tissue structures and neural elements in cervical spine disorders. T2-weighted sagittal sequences provide excellent visualisation of disc morphology, signal intensity changes indicative of degeneration, and the relationship between disc material and neural structures. The distinction between disc herniation and osteophyte formation can sometimes be challenging on T2-weighted images, leading to the use of the term disc osteophyte complex when the exact nature of the compressive pathology cannot be definitively determined. T1-weighted images offer superior anatomical detail and help identify areas of ossification within ligamentous structures or disc material. Axial sequences are particularly valuable for assessing the degree of central canal stenosis and neural foraminal narrowing, providing crucial information for surgical planning.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning provides excellent bony detail and is particularly useful for evaluating the extent and morphology of osteophytes at the C3-C4 level. High-resolution CT imaging can distinguish between calcified disc material and true bony osteophytes, information that is crucial for surgical planning and technique selection. CT myelography, whilst less commonly performed due to its invasive nature, can provide valuable information regarding spinal cord compression and cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics when MRI findings are equivocal or when patients have contraindications to MRI. Three-dimensional CT reconstructions offer excellent visualisation of complex anatomical relationships and can be particularly helpful for planning surgical approaches and understanding the spatial orientation of osteophytes relative to neural structures.

Conservative management strategies and interventional techniques

The initial management of disc osteophyte complexes at the C3-C4 level typically involves conservative approaches aimed at reducing inflammation, improving functional mobility, and preventing progression of symptoms. Physical therapy forms the cornerstone of conservative treatment

and encompasses a multimodal approach designed to address the specific impairments associated with C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes. Therapeutic interventions focus on restoring normal cervical spine biomechanics through targeted exercises that improve deep neck flexor strength and reduce excessive upper cervical extension patterns. Manual therapy techniques, including joint mobilisation and soft tissue release, can help restore segmental mobility and reduce muscle tension that often accompanies cervical spondylosis.

Postural correction represents a critical component of conservative management, particularly in patients with occupational or lifestyle factors contributing to cervical spine degeneration. Education regarding proper ergonomics, workspace setup, and sleep positioning can significantly impact symptom progression and treatment outcomes. Cervical traction, whether performed manually or mechanically, may provide temporary symptom relief by reducing compressive forces on neural structures and promoting disc height restoration. However, the effectiveness of traction must be carefully evaluated on an individual basis, as some patients may experience symptom exacerbation due to the complex nature of disc osteophyte pathology.

Pharmacological interventions typically begin with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to address the inflammatory component of disc degeneration and osteophyte formation. Neuropathic pain medications, such as gabapentin or pregabalin, may be beneficial for patients experiencing radicular symptoms due to C4 nerve root compression. Muscle relaxants can provide short-term relief for patients with significant cervical muscle spasm, though their long-term use should be avoided due to potential dependency and sedation effects. Topical preparations containing capsaicin or NSAIDs may offer localised relief with reduced systemic side effects compared to oral medications.

Interventional pain management techniques provide valuable treatment options for patients who do not respond adequately to conservative measures. Cervical epidural steroid injections can be particularly effective for managing radicular symptoms associated with C4 nerve root compression, providing both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits. The anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids can help reduce neural inflammation and oedema, potentially providing several months of symptom relief. Cervical facet joint injections may be considered when zygapophysial joint arthropathy contributes significantly to the clinical presentation, though their effectiveness for disc-related pathology is limited.

The success of conservative management depends heavily on patient compliance with prescribed therapies and the early identification of neurological deterioration that may warrant surgical intervention.

Surgical treatment options for refractory cases

When conservative management fails to provide adequate symptom relief or when progressive neurological deficits develop, surgical intervention becomes necessary for patients with C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes. The choice of surgical approach depends on several factors, including the location and extent of pathology, the presence of instability, bone quality, and patient-specific considerations such as age and comorbidities. Anterior approaches are generally preferred for addressing ventral pathology, including disc herniation and anterior osteophytes, whilst posterior approaches are more suitable for addressing facet joint arthropathy, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and posterior element pathology.

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) represents the gold standard surgical treatment for C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes with significant anterior compression. This procedure involves complete removal of the degenerated disc, decompression of neural structures through osteophytectomy, and restoration of disc height through interbody fusion. Modern ACDF techniques utilise titanium or PEEK (polyetheretherketone) interbody cages filled with autograft or allograft bone to promote fusion whilst maintaining cervical lordosis. The procedure typically achieves excellent clinical outcomes with fusion rates exceeding 95% when performed at single levels. However, the loss of motion at the treated segment can potentially accelerate degeneration at adjacent levels, a phenomenon known as adjacent segment disease.

Cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) has emerged as an alternative to fusion for select patients with C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes, particularly those with preserved facet joints and minimal instability. Motion-preserving surgery aims to maintain physiological kinematics at the treated level whilst addressing the pathological disc and associated osteophytes. Artificial disc devices are designed to replicate normal cervical spine motion patterns and potentially reduce the risk of adjacent segment degeneration compared to fusion procedures. However, patient selection criteria are more stringent for disc arthroplasty, and long-term outcomes data are still evolving compared to the extensive experience with ACDF procedures.

Posterior approaches, including laminoplasty or laminectomy with fusion, may be necessary for patients with predominantly posterior pathology or multilevel disease extending beyond the C3-C4 segment. Cervical laminoplasty preserves posterior cervical anatomy whilst expanding the spinal canal diameter, making it particularly suitable for patients with multilevel central stenosis. This procedure involves creating a “door” in the posterior elements that is held open with titanium plates or spacers, allowing decompression without destabilising the spine. Laminoplasty is associated with preservation of cervical motion, though some patients may experience reduced range of motion and axial neck pain postoperatively.

Combined anterior-posterior approaches may be required in complex cases with significant pathology involving both anterior and posterior elements of the C3-C4 motion segment. These procedures are typically reserved for patients with severe deformity, instability, or extensive osteophytic disease that cannot be adequately addressed through a single approach. Staged procedures, performed days to weeks apart, may be preferred over simultaneous anterior-posterior surgery to reduce operative time and minimise complications. The decision to pursue combined approaches requires careful preoperative planning and consideration of the patient’s overall medical condition and ability to tolerate prolonged anaesthesia.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are increasingly being applied to cervical spine pathology, including C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes. These approaches utilise smaller incisions, muscle-sparing techniques, and specialised instrumentation to achieve decompression whilst minimising soft tissue disruption. Endoscopic discectomy techniques allow targeted removal of disc material and small osteophytes through ports measuring only 6-8mm in diameter, potentially reducing postoperative pain and recovery time. However, the applicability of minimally invasive techniques depends on the specific anatomy and pathology present, and not all cases are suitable for these approaches.

Postoperative management following surgical treatment of C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes focuses on promoting healing, preventing complications, and optimising functional outcomes. Early mobilisation is encouraged to prevent complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pneumonia, though specific restrictions may apply depending on the surgical approach and fusion requirements. Physical therapy typically begins within days of surgery, initially focusing on gentle range of motion exercises and progressing to strengthening and functional activities as healing progresses. Rigid cervical orthoses are commonly prescribed following fusion procedures to protect the construct during the critical healing period, typically for 6-12 weeks postoperatively.

The success of surgical intervention for C3-C4 disc osteophyte complexes depends not only on technical surgical factors but also on appropriate patient selection, realistic expectations, and comprehensive postoperative rehabilitation.