Haemorrhoids occurring at the superior aspect of the natal cleft present a unique clinical scenario that often confounds both patients and healthcare practitioners. While most individuals associate haemorrhoidal disease with the traditional anatomical locations around the anal verge, the development of haemorrhoidal tissue at the top of the buttock crease represents a distinct pathological entity with specific aetiological factors. This particular manifestation frequently mimics other perianal conditions, leading to diagnostic challenges and potential delays in appropriate treatment.

The anatomical positioning of these lesions at the anococcygeal raphe creates a complex interplay between mechanical factors, vascular dynamics, and local tissue characteristics. Understanding the underlying mechanisms behind this specific presentation is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management. The condition affects thousands of individuals annually, yet remains poorly understood in mainstream medical literature, often being confused with pilonidal disease or other natal cleft pathologies.

Anatomical classification of haemorrhoids in the natal cleft region

The natal cleft region encompasses a complex anatomical area where multiple tissue planes converge, creating unique conditions for haemorrhoidal development. Traditional haemorrhoidal classification systems focus on the relationship between internal and external haemorrhoids relative to the dentate line, but lesions occurring at the superior buttock crease require a modified understanding of anatomical relationships.

External haemorrhoid formation at the anococcygeal raphe

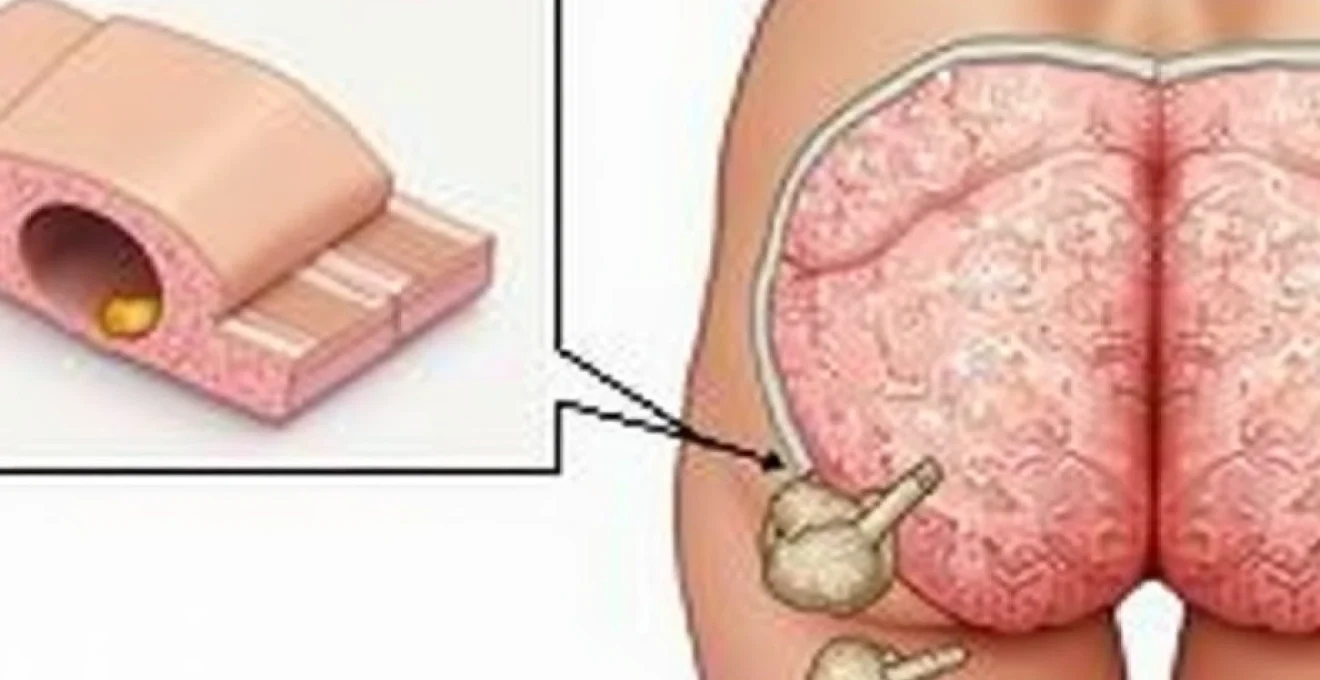

External haemorrhoids developing at the anococcygeal raphe represent a distinct subset of haemorrhoidal disease characterised by their position posterior to the anal opening. These lesions form due to dilatation of the subcutaneous external haemorrhoidal plexus extending into the natal cleft region. The anococcygeal raphe serves as a fibrous septum connecting the anal canal to the coccyx, providing a pathway for venous congestion to manifest in this unusual location.

The vascular anatomy in this region differs significantly from traditional haemorrhoidal locations, with venous drainage patterns following the posterior sacral veins rather than the typical superior and inferior rectal venous systems. This anatomical variation explains why haemorrhoids in this location may respond differently to conventional treatments and exhibit unique symptomatology patterns.

Thrombosed perianal haematoma differentiation

Distinguishing between true haemorrhoidal tissue and thrombosed perianal haematomas at the superior natal cleft requires careful clinical assessment. Thrombosed haematomas typically present as acute, painful, bluish-purple nodules that develop rapidly following episodes of increased intra-abdominal pressure. These lesions contain organised blood clots rather than the chronically dilated venous structures characteristic of true haemorrhoidal disease.

The temporal presentation differs markedly between these conditions, with thrombosed haematomas exhibiting acute onset pain that gradually subsides over several days, while true haemorrhoids at this location tend to demonstrate more chronic, intermittent symptoms. Proper differentiation is essential as treatment approaches vary significantly between these two conditions.

Posterior midline haemorrhoidal complex anatomy

The posterior midline represents a unique anatomical zone where haemorrhoidal tissue can extend beyond the traditional anal canal boundaries. This area corresponds to the six o’clock position in the lithotomy position and frequently demonstrates enlarged haemorrhoidal complexes that extend posteriorly into the natal cleft region. The venous drainage in this area follows both the internal and external haemorrhoidal plexuses, creating a transitional zone where symptoms may overlap.

Understanding the anatomical relationships in this region requires recognition of the anoderm extension and the transitional epithelium that characterises the posterior commissure. These tissue characteristics influence both symptom presentation and treatment response patterns in patients with posterior midline haemorrhoidal disease.

Anal papilla hypertrophy vs true haemorrhoidal disease

Hypertrophied anal papillae can occasionally extend posteriorly and mimic haemorrhoidal tissue at the superior natal cleft. These structures represent reactive hyperplasia of normal anal papillae in response to chronic inflammation or irritation. Unlike true haemorrhoidal tissue, hypertrophied papillae contain fibrous tissue rather than dilated vascular structures and typically demonstrate a more sessile attachment to the anal canal.

The distinction becomes clinically relevant when planning treatment strategies, as surgical management of hypertrophied papillae requires different techniques compared to haemorrhoidal excision. Accurate identification prevents inappropriate treatment approaches and optimises patient outcomes.

Pathophysiological mechanisms behind superior buttock crease haemorrhoids

Elevated Intra-Abdominal pressure and valsalva manoeuvre effects

The development of haemorrhoidal tissue at the superior natal cleft is intrinsically linked to episodes of elevated intra-abdominal pressure, particularly during Valsalva manoeuvres associated with defaecation, heavy lifting, or chronic coughing. These pressure increases are transmitted through the venous system, causing dilatation of the haemorrhoidal plexuses that extend posteriorly beyond the anal verge.

The anatomical configuration of the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels makes them particularly susceptible to pressure-related dilatation. Unlike the anterior and lateral positions, the posterior location lacks significant muscular support from the anal sphincter complex, making these vessels more prone to prolapse and enlargement during episodes of increased abdominal pressure.

Pelvic floor dysfunction contributing to venous congestion

Pelvic floor dysfunction creates a cascade of physiological changes that predispose to haemorrhoidal development in unusual locations. When the pelvic floor muscles fail to coordinate properly during defaecation, increased straining becomes necessary to achieve bowel evacuation. This chronic straining pattern leads to sustained elevation of intra-abdominal pressure and subsequent venous congestion in the haemorrhoidal plexuses.

The posterior aspect of the anal canal and natal cleft region becomes particularly vulnerable to venous congestion due to the confluence of multiple venous drainage pathways in this anatomical zone. Pelvic floor dysfunction disrupts the normal pressure gradients that regulate venous return, leading to stagnation and subsequent haemorrhoidal formation at atypical locations.

Chronic Constipation-Induced straining patterns

Chronic constipation represents one of the primary aetiological factors in the development of superior natal cleft haemorrhoids. The repetitive straining associated with difficult bowel movements creates sustained pressure increases that gradually dilate the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels. This process occurs over months to years, with progressive enlargement of the affected vessels until they become clinically apparent.

The pathophysiology involves not only the acute pressure increases during individual straining episodes but also the cumulative effects of chronic venous distension. The posterior haemorrhoidal plexus lacks the protective mechanisms present at other anatomical locations, making it particularly susceptible to this chronic pressure-related damage.

Portal hypertension secondary manifestations

Portal hypertension, whether due to liver disease, portal vein obstruction, or other causes, can manifest as haemorrhoidal disease at unusual anatomical locations, including the superior natal cleft. The portosystemic collateral circulation includes connections between the superior rectal veins and the internal iliac venous system, creating pathways for portal hypertension to affect the posterior haemorrhoidal plexuses.

Patients with portal hypertension may develop extensive haemorrhoidal disease that extends beyond the traditional anal canal boundaries, involving the entire circumference of the anal margin and extending posteriorly into the natal cleft region. This presentation requires specific consideration of the underlying systemic condition when planning treatment approaches.

Congenital and acquired risk factors for posterior haemorrhoidal development

The development of haemorrhoids at the superior buttock crease involves a complex interaction between congenital predisposing factors and acquired risk elements. Congenital factors include inherited variations in venous wall structure, collagen composition abnormalities, and anatomical variants in the posterior haemorrhoidal vascular anatomy. These genetic predispositions create a foundation upon which environmental and lifestyle factors can precipitate clinical haemorrhoidal disease.

Acquired risk factors demonstrate significant diversity and often work synergistically to promote haemorrhoidal development. Occupational factors play a particularly important role, with prolonged sitting occupations creating sustained pressure on the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels. The modern sedentary lifestyle compounds this risk, as reduced physical activity leads to decreased venous return and increased susceptibility to venous stasis in the pelvic region.

Pregnancy represents a unique risk scenario where multiple factors converge to increase haemorrhoidal risk at all anatomical locations, including the posterior natal cleft region. The combination of increased blood volume, hormonal changes affecting vascular tone, and direct pressure from the gravid uterus creates optimal conditions for haemorrhoidal development. The posterior location becomes particularly vulnerable during the second and third trimesters when pelvic pressure reaches maximum levels.

Dietary factors contribute significantly to posterior haemorrhoidal development through their effects on bowel function and stool consistency. Low-fibre diets promote constipation and hard stool formation, necessitating increased straining during defaecation. This straining pattern specifically affects the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels due to their anatomical positioning and relative lack of muscular support compared to anterior and lateral locations.

The interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors determines not only the likelihood of haemorrhoidal development but also the specific anatomical locations where symptoms will manifest most prominently.

Differential diagnosis of posterior anal margin lesions

Anal Fissure-Associated sentinel piles

Posterior anal fissures frequently develop sentinel piles or skin tags that can be mistaken for haemorrhoidal tissue at the superior natal cleft. These sentinel piles represent reactive tissue formation in response to chronic anal fissure inflammation and typically demonstrate a more fibrous consistency compared to true haemorrhoidal tissue. The association with anal fissure symptoms, including severe pain during and after defaecation, helps differentiate these lesions from primary haemorrhoidal disease.

The temporal relationship between fissure symptoms and sentinel pile development provides important diagnostic clues. Patients typically report an initial period of severe anal pain followed by the gradual development of a posterior skin tag or pile. This progression differs markedly from primary haemorrhoidal disease, which tends to develop more gradually without the acute pain phase characteristic of anal fissures.

Pilonidal sinus disease mimicking haemorrhoidal symptoms

Pilonidal sinus disease represents the most challenging differential diagnosis for haemorrhoids occurring at the superior natal cleft due to overlapping anatomical locations and similar presenting symptoms. Pilonidal disease typically affects the sacrococcygeal region and can extend into the upper portion of the natal cleft, creating diagnostic confusion with posterior haemorrhoidal disease.

Key differentiating features include the presence of hair-containing sinuses or pits in pilonidal disease, which are absent in true haemorrhoidal conditions. Additionally, pilonidal disease tends to affect younger males more frequently and often demonstrates episodic inflammatory flares rather than the chronic, progressive symptoms typical of haemorrhoidal disease. Careful physical examination revealing sinus openings or hair-containing pits confirms the diagnosis of pilonidal disease rather than haemorrhoidal pathology.

Perianal abscess formation in the posterior commissure

Perianal abscesses developing in the posterior commissure can mimic acutely thrombosed haemorrhoids at the superior natal cleft. These abscesses typically arise from infected anal glands and demonstrate rapid onset with severe, constant pain and systemic symptoms including fever and malaise. The presence of fluctuance on palpation and the acute nature of symptom development help differentiate abscess formation from haemorrhoidal disease.

The management approaches differ significantly between these conditions, with perianal abscesses requiring urgent surgical drainage while haemorrhoidal disease can often be managed conservatively initially. Proper diagnosis prevents inappropriate treatment delays that could lead to abscess extension or systemic complications.

Condyloma acuminata localisation patterns

Anal condylomata can occasionally develop at the posterior anal margin and extend into the natal cleft region, creating potential confusion with haemorrhoidal tissue. These viral-induced lesions demonstrate characteristic cauliflower-like morphology and tend to be more superficial than haemorrhoidal tissue. The viral aetiology means that condylomata often present as multiple lesions rather than the solitary or paired lesions typical of posterior haemorrhoidal disease.

The differentiation becomes important for treatment planning, as condylomata require antiviral or immunomodulatory approaches rather than the mechanical treatments used for haemorrhoidal disease. Additionally, the infectious nature of condylomata necessitates partner evaluation and safe sexual practices that are not relevant to haemorrhoidal management.

Hormonal and physiological contributors to natal cleft haemorrhoids

Hormonal influences play a significant role in the development and exacerbation of haemorrhoidal disease at all anatomical locations, including the superior natal cleft region. Oestrogen and progesterone fluctuations during menstrual cycles affect vascular tone and venous capacitance, influencing the propensity for haemorrhoidal vessel dilatation. These hormonal effects are particularly pronounced during pregnancy when hormone levels reach peak concentrations and sustained elevation.

The physiological changes associated with pregnancy create a perfect storm for posterior haemorrhoidal development. Increased blood volume places additional strain on the venous system, while progesterone-induced smooth muscle relaxation reduces venous tone and promotes vessel dilatation. The growing uterus applies direct pressure to the pelvic venous system, creating mechanical obstruction to venous return that particularly affects the posterior haemorrhoidal drainage pathways.

Menopausal changes also influence haemorrhoidal disease patterns, with declining oestrogen levels affecting collagen synthesis and vascular wall integrity. This hormonal transition can lead to weakening of the supporting structures around haemorrhoidal vessels, making them more susceptible to prolapse and enlargement. Understanding these hormonal influences helps explain why haemorrhoidal disease often demonstrates cyclical patterns of exacerbation and remission in reproductive-age women.

Thyroid dysfunction represents another hormonal factor that can influence haemorrhoidal development through its effects on bowel motility and cardiovascular function. Hypothyroidism commonly causes constipation, leading to increased straining and subsequent haemorrhoidal formation, while hyperthyroidism can cause diarrhoea that may irritate existing haemorrhoidal tissue and promote inflammation.

Hormonal fluctuations create a dynamic environment where haemorrhoidal symptoms may vary significantly based on endocrine status, requiring individualised treatment approaches that consider these physiological variations.

Occupational and lifestyle factors precipitating superior buttock haemorrhoidal disease

Modern occupational patterns significantly contribute to the development of haemorrhoidal disease at unusual anatomical locations, with prolonged sitting representing the primary risk factor for superior natal cleft presentations. Office workers, professional drivers, and individuals in sedentary occupations experience sustained pressure on the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels due to prolonged sitting postures. This mechanical pressure impedes venous return and promotes stagnation in the haemorrhoidal plexuses, particularly affecting the posterior vessels that lack significant muscular support.

The ergonomic factors associated with modern work environments compound these risks through poor seating design, inadequate lumbar support, and prolonged periods without position changes. Traditional office chairs concentrate pressure at the posterior pelvis, creating focal points of increased pressure directly over the haemorrhoidal vessels. The lack of regular movement breaks prevents the natural pumping action that promotes venous return and reduces stagnation in the pelvic venous system.

Athletic activities present a paradoxical relationship with haemorrhoidal development, where certain sports increase risk while others provide protective benefits. Weightlifting, powerlifting, and activities involving significant Valsalva manoeuvres create acute spikes in intra-abdominal pressure that can precipitate haemorrhoidal formation or exacerbation. Conversely, aerobic activities that promote cardiovascular fitness and regular bowel function provide protective effects against haemorrhoidal development.

Cycling and equestrian sports demonstrate particular relevance to posterior haemorrhoidal development due to the sustained pressure applied to the perineum and natal cleft region. The saddle design in these activities creates focal pressure points that directly compress the posterior haemorrhoidal vessels, while the repetitive motion can cause additional mechanical irritation. Professional cyclists often develop characteristic patterns of haemorrhoidal disease that predominantly affect the posterior anal margin due to these specific biomechanical factors.

Dietary lifestyle patterns significantly influence haemorrhoidal development through their effects on bowel function and inflammatory processes. Processed food consumption and refined carbohydrate intake promote constipation and reduce beneficial gut bacteria populations, creating conditions that favour haemorrhoidal formation. The lack of dietary fibre reduces stool bulk and promotes straining during defaecation, while excessive consumption of spicy foods, alcohol, and caffeine can increase anal irritation and promote inflammatory responses in existing haemorrhoidal tissue.

Sleep patterns and circadian rhythm disruptions affect haemorrhoidal disease through their influence on digestive function and hormonal regulation. Shift workers and individuals with irregular sleep schedules often experience disrupted bowel patterns that contribute to constipation and subsequent haemorrhoidal development. The hormonal dysregulation associated with poor sleep quality affects collagen synthesis and vascular integrity, potentially weakening the supportive structures around haemorrhoidal vessels.

The modern lifestyle creates a convergence of risk factors that particularly predispose to haemorrhoidal development at atypical locations, requiring comprehensive lifestyle modifications rather than purely medical interventions for optimal management outcomes.

Stress management represents an often-overlooked factor in haemorrhoidal disease development and management. Chronic psychological stress affects gut motility through the gut-brain axis, often manifesting as either constipation or diarrhoea patterns that can exacerbate haemorrhoidal symptoms. The physiological stress response also includes increased muscle tension in the pelvic floor region, which can impair normal defaecation patterns and promote straining behaviours that contribute to posterior haemorrhoidal formation.